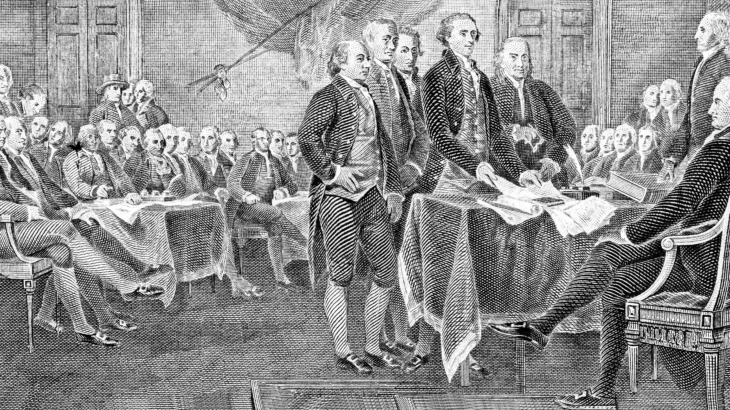

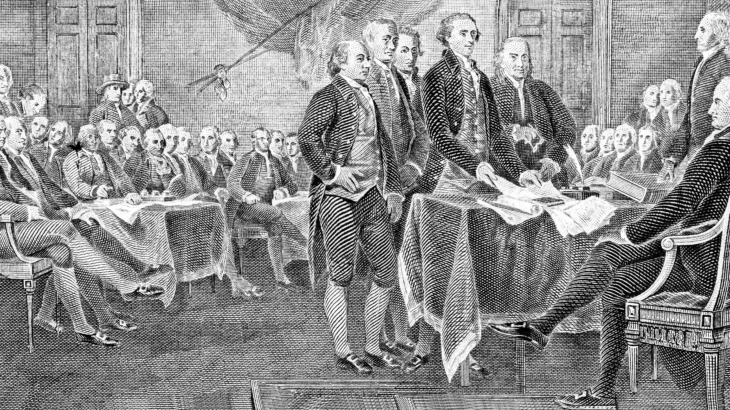

The “right of the people to alter or abolish” their government is derived from our natural right to self-governance. The notion of self-governance is relatively new. In 1776, the world was ruled by royalty or warrior chieftains. Some upstart colonialists then penned the most revolutionary document in the history of man. Kings and queens no longer enjoyed a Divine Right to rule. Instead, the individual was now the one endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights. Like most revolutionary visions, this one didn’t suddenly spring onto the world stage. Baron de Montesquieu, John Locke, David Hume, Adam Smith, Thomas Paine, and many others had advocated that “consent of the governed” was dictated by the laws of nature and of nature’s God. Of course, not everyone accepted this concept—certainly not King George III or English nobility. It took seven years of warfare for the colonies to solidify their claim of self-governance.

“The infant periods of most nations are buried in silence, or veiled in fable, and perhaps the world has lost little it should regret. But the origins of the American Republic contain lessons of which posterity ought not to be deprived.” — James Madison

The Founders, however, were steeped in this incendiary idea. Self-governance had been part of their experience in the New World. The colonists were subjects of England, but a round-trip sail across the great Atlantic put three to four months between them and their king. Self-rule started with the Pilgrims. The Mayflower Compact began by pledging loyalty to King James, but then decreed that the colonists would

“combine together into a civil body politick, for our better ordering and preservation, and furtherance of the ends aforesaid: and by virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal laws, ordinances, acts, constitutions, and officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most convenient for the general good of the colony.”

Basically, the Mayflower Compact was a written statement declaring self-government in colonial America.

“under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government” —Declaration of Independence.

Geography may have allowed the early colonists to govern themselves, but it was the writings of the Enlightenment that declared that self-rule was a natural right. This grand idea eventually led to the Declaration of Independence, which asserted that it was the right of the people “to institute a new government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.” This founding principle basically said that the people themselves held the power to form a new government at any time and in any shape that met their needs. It was a radical concept used to justify radical action.

The power to “institute a new government” also conveys the power to “alter or to abolish it.” The 1787 replacement of the Articles of Confederation with our Constitution is a historical example of this concept. Since that date, we have not seen a need to abolish our government because we have been able to alter it continuously with amendments, laws, and political movements.

Our government at the national level is not a direct democracy. (Half of the states allow ballot initiatives which, if passed by a majority of the voters, have the force of law.) Instead, we elect representatives to write laws and a president to administer those laws. When the people’s will is thwarted, regular elections give them the opportunity to dismiss their representatives and appoint new ones. As a further safeguard, our government theoretically only has powers delegated by the people, reinforcing the concept that power resides with the people, not political leaders. The principle of self-governance is echoed in the 9 th and 10 th Amendments to the United States Constitution.

As long as people believe their voices count, fair and honest elections prevent the more drastic action of abolishment. Revolutions are bred when people believe their voices go unheard, especially in periods of hardship.

James D. Best is the author of Tempest at Dawn, a novel about the 1787 Constitutional Convention, Principled Action, Lessons From the Origins of the American Republic, and the Steve Dancy Tales.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn